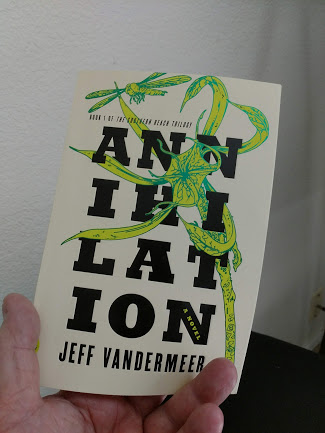

How to Write Creepy: Five Lessons from Annihilation by Jeff VanderMeer

The Lessons

I just read Annihilation again and it’s got me thinking…

Who doesn’t like a little creepy in what they read? The small and sneaky way it moves up the page.

We’ve seen bad spooky writers. Authors who mistake spectacle for scare? Showy monsters, uglier than ugly.

I prefer my spook a little quieter, so that it lingers like clammy breath inside tight quarters. Shirley Jackson’s wrote like that. So does Jeff VanderMeer in his first novel of the Southern Reach Trilogy, Annihilation.

Here’s how.

Creepy Lesson #1: Keep the Characters at a Distance

Venturing into the mysterious Area X, we only know Annihilation’s all-female cast by what they do. These women have no names, and are known only by their functions and professions—the biologist, the psychologist, the surveyor, and the anthropologist.

Very sterile.

We hear the instructions they were given, as told by the biologist. “We were meant to be focused on our purpose, and ‘anything personal should be left behind.’ Names belonged to where we came from, and not to who we were once embedded in Area X.”

Even the place name, Area X, doesn’t tell the reader much about it. Nor do the characters tell the reader much about themselves. Nor do they tell one another.

There is no intimacy, no camaraderie, no closeness between them. Closeness interferes with purpose. The women’s communication is cold and detached. Just the facts, ma’am, and the facts cannot be trusted. Early in Area X when the biologist inhales some organism growing from words on a wall, she confides it to no one. Confidences breed suspicion. In Area X, better not to be seen.

All so cold. All so pseudoscientific and disengaged. You wonder why they’re there with one another in the first place. What’s their purpose?

Creepy Lesson #2: A Dysfunctional Team

Everyone for themselves. Good mysteries do this. Characters team up with characters whose interests are at odds with one another’s. Agatha Christie’s Ten Little Indians or Olen Steinhauser’s The Cairo Affair. Suspense woven out of competition to win. To survive. The rocky distrust of shared disharmony.

Annihilation’s team supposedly shares a goal. To explore Area X. They depend on one another’s expertise. Perhaps, together they might discover their environment’s mystery. They might learn what happened to earlier expeditions who never returned, and why those who did return behaved so differently than before they went in. The biologist’s husband was one. He was on the expedition immediately preceding his wife’s. She doesn’t tell the others this. It even takes a while for her to confine it to us, the readers. What is she doing there on this Expedition #12? What’s her purpose?

The longer she and her teammates venture into Area X the less purposeful their mission becomes. They argue. They turn on one another. Are they there to observe, or to be observed. Are they the control element of this experiment, or the variable? It gets a little murky.

The biologist, she’s our narrator. Can we trust her?

Creepy Lesson #3: The Unreliable Narrator

Like marriages and stray pets, it’s creepy to discover someone you trust cannot be trusted. Henry James’ The Turn of the Screw plays with this. In Annihilation, the biologist seems quite straightforward, factual, observational, focused. Very black and white in what she says.

Until we learn she’s not. She makes odd comments without speculating or challenging herself about them. Trying to explain how they arrived at Area X, she dismissively explains that the psychologist had “put us all under hypnosis to cross the border.” Is the biologist hypnotized now as she tells us this? Can she know?

Her unemotional reporting from Area X begins to sound vague and incurious. Speculating how long the mission might last, she says it could be either days, months, or years “depending upon various stimuli and conditions.” She reports there are six kinds of “poisonous snakes in Area X.” But she’s a biologist. Shouldn’t she call them venomous and not poisonous? She says at one point “Curiosity can be a powerful distraction.” It’s what someone hypnotized might say. Don’t ask. Conform to the hypnosis. Except she insists hypnosis does not effect her? She says she’s the only one of the team that can’t be hypnotized. And yet, has her blind spots.

Creepy Lesson #4: See only What We’re Hypnotized to See

So much of Annihilation is just that. A study about comprehending only what our minds already understand.

Throughout the book, the biologist assigns meaning to her experience by being able to identify its purpose. When they first encounter the underground tunnel (the biologist insists on calling it a tower), she wonders what is its purpose. When inside the tunnel (tower?) she encounters a string of words composed of living matter and slithering the walls, she says, “Even though I didn’t know what the words meant, I wanted them to mean something so I might more swiftly remove doubt.”

Our need to comprehend is a form of control we try exercising. The way we fit experience into a familiar box of our own making. Reasoning with words and prejudice to create a comforting, abstract order out of natural chaos. Giving all that we encounter a name. Finding its utility, so that the thing itself disappears. So that it transmutes into order.

Thomas Merton once said, “Do not cling to the delusion of expectation.”

Expectation imagines ghosts. Those bits our minds see that we cannot comprehend. Haunting specters of disorder that we prefer to ignore.

Some readers call Annihilation sci fi. I call it an environmental horror story. Either way it scolds us. It scolds our environmental responsibility to be stewards of the earth. It scolds our delusions. We are not at the top of the food chain. We co-exist within it, feeding on it while being fed upon.

Creepy Lesson #5: A Living Environment is an Environment at Odds with Ourselves

There is no order, no expectation, no matter how much we crave it. There is no natural progression of things. Only the chaos of arising and descent. Ebb and flow. A rhythm in which we partake, but do not command.

A Buddha once said, “The greatest myth humans concoct is the delusion of belief. It creates non-existence, and seduces us into believing it.”

That’s creepy, in an Annihilation kind of way.

2 thoughts on “How to Write Creepy: Five Lessons from Annihilation by Jeff VanderMeer”

אני מאוד ממליץ על אתר ישראל נייט קלאב אתר מספר אחד בישראל לחיפוש נערות ליווי, דירות דיסקרטיות,עיסוי אירוטי

כנסו עכשיו ותראו לבד כמה מידע יש באתר הזה: נערות ליווי בחיפה

delta airlines reservation desk https://ffs2play.fr/question/1855670-2491-delta-airlines-reservation-desk/

Comments are closed.